You've been driving for decades. You could navigate your daily commute half-asleep. But somehow, the moment your teenager slides into the driver's seat, every bit of that experience feels useless.

That's because knowing how to drive and knowing how to teach your teenager to drive are completely different skills. And here's what nobody tells you: the anxiety you're feeling right now? It's not a sign that something's wrong with you. It's a sign that you understand the stakes.

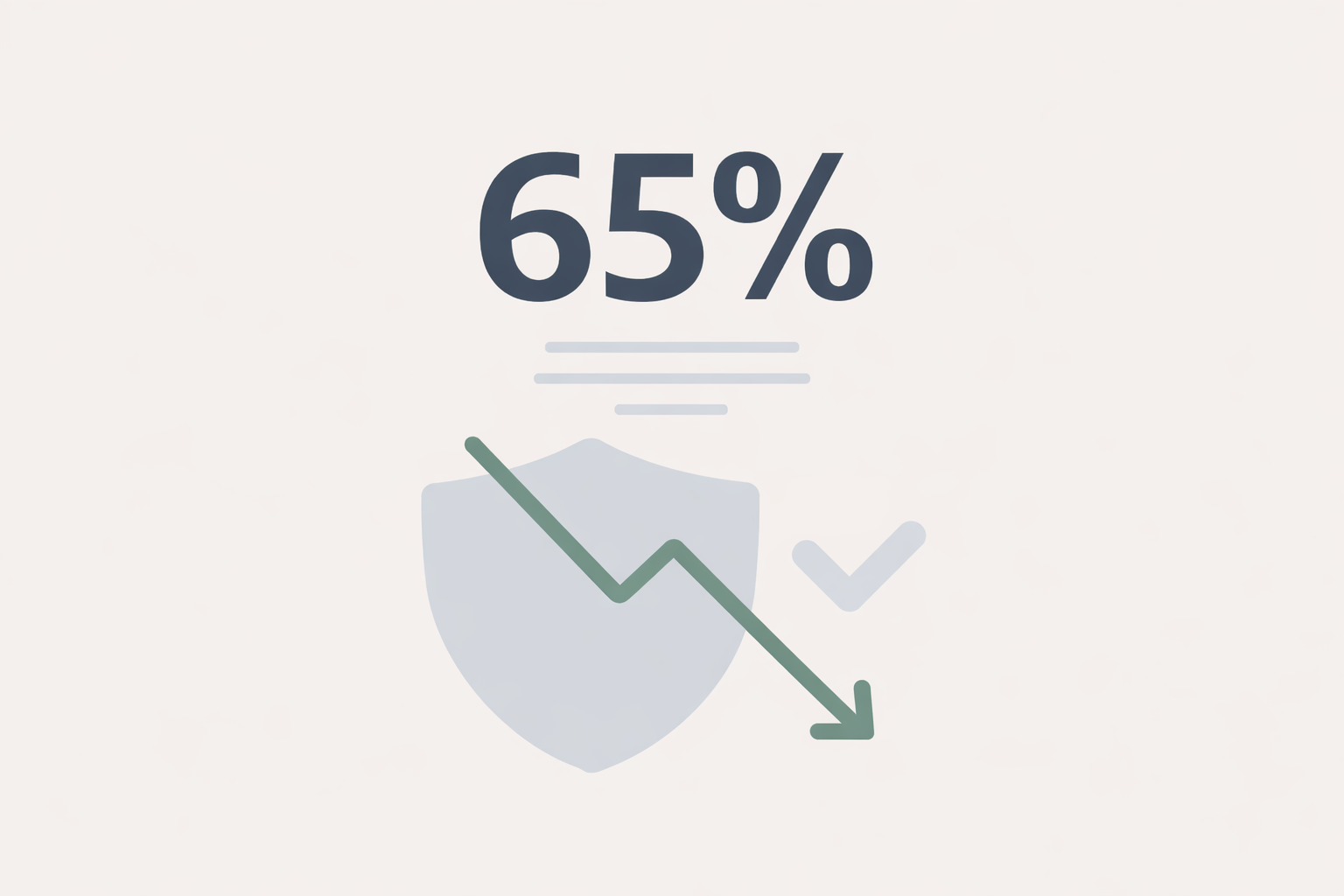

The good news is this doesn't have to end in screaming matches at intersections or practice sessions that leave you both in tears. Research from Children's Hospital of Philadelphia shows that parents who follow a structured approach can reduce their teen's dangerous driving errors by 65%. That's not a small number—that's the difference between close calls and safe arrivals.

This guide will show you why teaching your teen feels so hard (it's not your imagination), what's actually happening in their brain, and how to become the calm, effective driving coach your teen needs—even when every instinct is telling you to grab the wheel.

Why Teaching Your Teen to Drive Feels So Hard

If you've ever thought "Why does this feel impossible?"—you're not imagining things. There's a biological reason this is difficult, and it has nothing to do with your parenting skills or your teen's attitude.

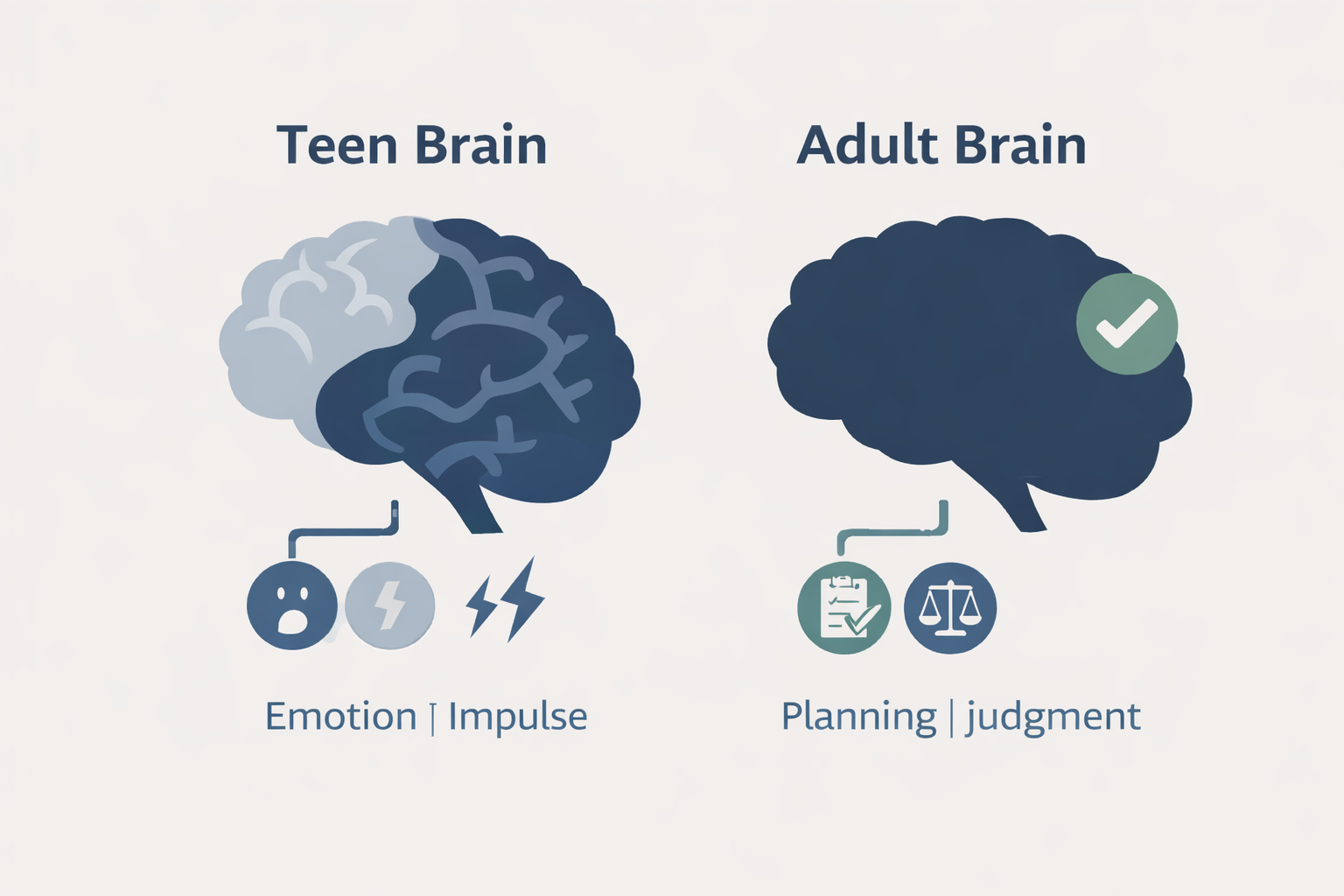

The prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for risk assessment, impulse control, and decision-making—doesn't fully mature until around age 25, according to research published in the NIH's PubMed Central. Read that again. Age 25. Your teenager's brain is literally wired differently than yours.

This creates what researchers call a dangerous imbalance. The limbic system (emotions and reward-seeking) develops years ahead of the prefrontal cortex. The result: teens favor behaviors driven by emotion over rational decision-making—especially under pressure. This isn't defiance. It's neurobiology.

Here's where it gets even more important. A study from the Annenberg Public Policy Center found that working memory—the ability to track multiple things simultaneously while driving—develops at different rates in different teens. Some 16-year-olds have the cognitive capacity for complex driving tasks. Others won't develop it until their early twenties.

This explains the moment that terrifies every parent: your teen handles an empty parking lot perfectly, then makes a dangerous decision at a busy intersection. It's not that they weren't paying attention. It's that their brain literally couldn't process everything fast enough.

Understanding this changes everything. You're not fighting your teen's attitude—you're working with their developing brain. And that requires a different approach than simply logging hours behind the wheel.

The Confidence-Competence Gap (Why Your Gut Feeling Is Right)

You've probably sensed it already—that unsettling feeling that your teen thinks they're more ready than they actually are. Trust that instinct. The research confirms it.

According to a Liberty Mutual/SADD study, 75% of teens report being confident in their driving ability, and 77% believe they're safer than their peers. Yet 57% of high school seniors have already been in crashes or near-misses.

The math doesn't add up. And there's a reason.

Each uneventful drive actually reinforces overconfidence. Your teen's perception of risk decreases while their perception of their abilities increases—regardless of their actual skill level. They're not being arrogant. Their brain is doing exactly what it's designed to do: building confidence through repetition. The problem is that confidence is outpacing competence.

"Each time the teen takes an uneventful drive, his or her perception of the riskiness of driving goes down while perception of the benefits goes up," explains the NCBI's review of teen driving research. "The result is a teen who believes he or she can handle hazardous situations, is overconfident of his or her driving skills, and is decreasingly vigilant about safety."

This is why that nagging worry you feel isn't paranoia—it's pattern recognition. You've seen thousands of driving situations your teen hasn't encountered yet. Your brain knows what they don't know.

The question is: how do you build genuine competence before their confidence convinces them they're ready?

Coaching vs. Criticizing: The Shift That Changes Everything

Here's a truth that might sting a little: most parents are accidentally making this harder than it needs to be.

Most of us default to telling our teen what to do. That's natural—you've been giving instructions for 16 years. But driving instruction requires a fundamentally different approach. And the difference isn't subtle.

"As parents, we're so used to telling our children what to do," explains professional driving instructor Todd Avery. "But when it comes to driving, we need to coach them. Telling them what to do will only help them know how to operate a car. Coaching involves asking questions; getting teens to think for themselves."

Here's the part that surprised researchers at the University of North Carolina: teens often report dealing with "screaming parents" even when parents never raised their voices. Your tension—even unexpressed—triggers their fight-or-flight response, shutting down the cognitive processes needed for learning.

Think about that. You might be perfectly calm on the outside, but if you're gripping the door handle or tensing up at every intersection, your teen's brain registers threat. And a brain in threat mode can't learn.

The shift from "telling" to "coaching" involves several specific changes:

- How you give directions in the moment

- The words you choose (some common phrases actually create confusion)

- When you give feedback (timing matters more than you'd think)

- How you handle mistakes without triggering defensiveness

Most parents have never been taught how to teach. That's not a criticism—it's just reality. Driving is one of the first times you're asked to be an instructor, not just a parent. And the two roles require very different skills.

The good news? These are learnable skills. And learning them might be the most important thing you do for your teen's safety.

You Need a System, Not Just Practice Hours

Here's what most parents get wrong: they think teaching their teen to drive means logging hours behind the wheel until it "clicks."

But unstructured practice can actually reinforce bad habits and build false confidence. More hours doesn't automatically mean more skill—especially if those hours are spent repeating the same comfortable routes.

Research from CHOP's TeenDrivingPlan reveals something that should get every parent's attention: teens whose families followed a structured, progressive approach were 65% less likely to make dangerous driving errors. Not 10%. Not 20%. Sixty-five percent.

The key word is progressive—starting with foundational skills in low-risk environments and advancing only when genuine competence is demonstrated.

Think of it like building a house. You don't start with the roof. You pour the foundation, frame the walls, then work your way up. Each stage depends on the one before it. Skip a step, and the whole structure is compromised.

The same principle applies to driving instruction:

- Start in controlled environments where mistakes don't have consequences

- Build foundational skills before adding complexity

- Advance only when ready—not when your teen feels ready, but when they demonstrate consistent competence

- Progress through increasingly challenging situations in a deliberate sequence

The difference between parents who struggle through this process and parents who actually enjoy it often comes down to one thing: having a clear roadmap. Knowing exactly what skills to build at each stage. Understanding how to recognize when it's time to move forward—and when it's not.

Without that structure, you're guessing. And when it comes to your teen's safety, guessing isn't good enough.

How Many Hours Does Your Teen Actually Need?

State requirements vary—most mandate 40-50 hours of supervised practice. But here's something most parents don't realize: research suggests these minimums aren't enough.

AAA recommends at least 100 hours of supervised driving practice before licensing. The research consensus from CHOP's TeenDrivingPlan suggests 65-120 hours is optimal.

But here's the insight that matters more than any number: a NHTSA study found that whether 50 or even 60 hours produces measurable crash reduction remains uncertain. What matters more than total hours is how your teen practices.

Progressive skill building across varied conditions beats repetitive driving on familiar routes. Every time.

And here's something that keeps safety researchers up at night: the most dangerous period for teen drivers is the first three months after licensing. Research from NIH shows crash risk during this period is 8 times higher than during the learner's permit stage.

Eight times higher. That's not a typo.

This is why continued supervised practice after licensing matters—even after your teen legally can drive alone. The permit phase is just the beginning.

"Continue to practice supervised driving until your teen logs at least 100 hours," advises AAA Exchange. "Your teen might obtain an intermediate driver license before completing 100 hours of practice driving. This does not mean your teen driver no longer needs to practice."

The Statistics That Matter (And What You Can Do About Them)

Let's talk about the numbers—not to scare you, but to show you why your involvement matters so much.

Teen drivers are nearly 3 times more likely to die in a crash per mile driven compared to drivers age 20 and older, according to IIHS data. The first year of licensed driving is statistically the most dangerous year of your child's life behind the wheel.

But here's what those headlines often miss: this isn't inevitable.

CHOP research shows that 75% of serious teen crashes result from just three "critical errors"—failure to scan for hazards, going too fast for conditions, and being distracted. All three are directly addressable through proper training.

Properly implemented graduated licensing systems reduce youngest drivers' crash risk by 20-40%. Parents who stay actively involved—setting rules, practicing regularly, modeling good behavior—can cut their teen's crash risk in half, according to NHTSA research.

Read that again: cut crash risk in half.

You're not powerless here. Your involvement isn't helicopter parenting—it's the single most effective safety intervention that exists for teen drivers. The question isn't whether to be involved. It's how to be involved effectively.

What "Ready" Actually Looks Like

State minimums for licensing don't equal actual readiness. Passing the DMV test means your teen can operate a vehicle and follow basic rules. It doesn't mean they've developed the automatic responses that keep experienced drivers safe.

True readiness looks different than most parents expect. It's not about confidence—in fact, overconfidence is often a warning sign. It's about observable behaviors: consistent hazard scanning without prompting, calm responses to unexpected situations, self-correction without your input.

"Driving is a privilege, not a rite of passage," notes Dr. Flaura K. Winston, founder of CHOP's teen driver research program. "Only you know for sure when your child is ready to drive alone without parent supervision."

The challenge is knowing what to look for. Most parents rely on gut feeling or simply wait until their teen completes state-required hours. But there are specific, observable indicators that distinguish a teen who's genuinely ready from one who's just accumulated time behind the wheel.

And knowing those indicators might be the difference that matters most.

Your Next Step

Teaching your teenager to drive is one of the most important things you'll do as a parent. The stakes are real—the first year of licensed driving is statistically the most dangerous year of your child's life behind the wheel.

But it doesn't have to feel like chaos. And it definitely doesn't have to damage your relationship.

With the right understanding of what's happening in your teen's brain, the right approach to coaching (not criticizing), and a structured progression that builds genuine competence, you can guide your teen through this milestone. You can be the calm they need—even when your own heart is racing.

That's exactly what our course is designed to help you do.

Start with Module 1—completely free. You'll learn the neuroscience behind why teens struggle with driving (and why it's not attitude), the three risk factors behind most teen crashes, and a communication framework you can start using immediately.

No credit card required. Just practical strategies backed by research—and the first step toward becoming the driving coach your teen needs.

Get Free Access to Module 1